Diamond cuts and shapes can be hard to navigate. After all, who has time to sit all day in front of a computer or book and read through thousands of pages on cuts, clarities, symmetry, and styles? Well, we do. We’ve put this brief guide together for you so you don’t have to be up late at night trying to figure out the difference between Asscher and emerald cuts, or what style would look good on your finger.

Shape Vs. Cuts

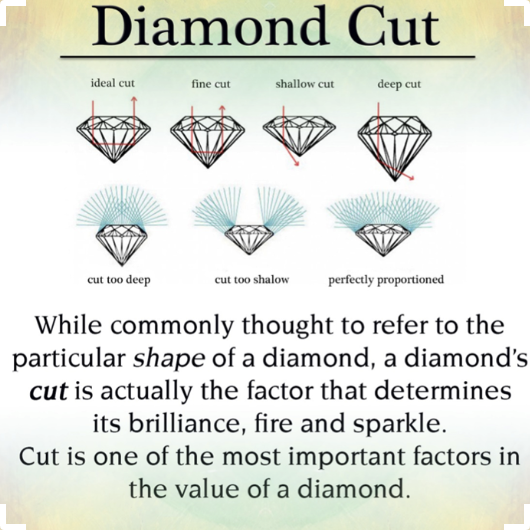

First off, let’s settle this: cuts and shapes aren’t the same thing. In fact, they’re very different.

Diamond shape is on the outside. It’s the style of the diamond, the aesthetic you want when you show off your new engagement ring.

The cut is on the inside, it’s what reflects light and where. This determines how bright or dull the actual stone looks.

Cuts

As mentioned before, diamond cuts are what determines the shine or brilliance of a stone.

If the stone is too shallow or deep, the light will get lost in the bottom. There needs to be an ideal number of facets and angles to properly reflect light back to your eyes. There isn’t a one-number-fits-all that will cause diamonds to shine – it depends on the cut. As well, you can’t have too many or too few. Diamonds are more than just glitter, there’s a whole science behind it (but that’s a blog post for another day).

Shapes

There are tonnes of different shapes and cuts to choose from, but for the purpose of this blog, we’ll stick to the more common ones.

Some people think shape doesn’t matter, but again, there’s quite a bit to consider before purchasing. Shape affects how the ring will sit on a finger. Pear and marquise shapes give the appearance for longer fingers, while princess and round make them look shorter. With that in mind, there’s no harm in playing around with different styles.

Round

This is one of the oldest and most popular shapes for diamonds. It was first developed by Marcel Tolkowsky in 1919. Considering that this shape gives the flexibility for diamonds to look their brightest, it makes sense. This traditional look is a very safe choice, and you can bet it won’t be going out of style any time soon – if ever.

Princess

Princess cut diamonds are a great choice for someone who wants a traditional look or a coloured band. The cut was first made in the early 1960s, making it a bit of a newer style. Nonetheless, this diamond cut is great because unlike most cuts, this one allows for light to shine through every corner, rather than just the centre. The nice thing is that this cut if available in rectangle and square in case you were looking for it to sit on your finger a particular way.

Emerald

The emerald cut offers a large view of the diamond because of the wide face. It makes for a very classy look in a modern way – even though it’s centuries old. The history of this cut goes back to the 1500s when the cut was originally used on emerald stones. That’s because there’s less pressure used to create the look with fewer chips in the stone. Either way, if you’re looking for something to make your fingers look longer, this is the cut for you!

Asscher

The Asscher cut was created in 1902 by Joseph Asscher, of the original Asscher Diamond Company. Up until the late 1930s, the company held the exclusive patent – and that’s when sales became stronger internationally. This elegant style is famously recognized because of Elizabeth Taylor’s Skupp Diamond. Many other celebrities prefer this style, and it’s believed to be one of the more common diamond cuts amongst celebrities.

Marquise

Of all the diamond cuts, the marquise is one of the best to max out carat weight and emphasize the size of a diamond. Despite looking very modern and sleek, there’s a very old history behind it. In the 18th century when King Louis XV was in power, he hired a jeweller to design a cut that was similar to the shape of Jean Antoinette Poisson, the Marchioness Madame de Pompadour. The name Marquis is a hereditary rank between count and duke and the diamonds they wore as a status symbol.

Oval

The oval cut is brilliant like a round but good for short fingers. It makes smaller diamonds look larger because of the cut, and while it isn’t the softest look, it still is very romantic. The oval cut was created in1957 by a Russian diamond cutter. Lazare Kaplan was born into a family of jewellers, giving him the chance to grow up within the industry, especially his uncle Abraham Tolkowsky, the inventor of the Ideal Cut. Prior to this, Kaplan was also known for other skills like cleaving. The oval cut got Kaplan into the Jewelers International Hall of Fame

Radiant

The cut corners give the diamond a unique look with lots of colour. The first Radiant cut was designed by Henry Grossbard in 1977 of The Radiant Cut Diamond Company. The company is still active, so you can purchase diamonds from the original creator. Even if you don’t, the radiant is one of the more elegant diamond cuts and will be sure to look good on or off your finger.

Pear

The pear cut offers maximum brilliance and makes smaller stones look larger. It also holds colour better than other cuts and is an overall more stylish design. It was first created in 1475 by the Flemish cutter, Lodewyk van Bercken. van Bercken was also known for having invented the scaif. This invention changed the diamond industry and how diamonds are polished, allowing for more complex designs.

Heart

The heart is a more soft and modern look – it’s also one of the hardest diamond cuts to pull off. This shape also started off as a symbol of royalty. The Duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, was the first to come up with the idea in 1463. He was talking about the quests of Cosimo di Medici.

Cushion

This shape got its name because of the resemblance to a pillow. Similar to other shapes mentioned here, the larger facets and round corners make for a more brilliant appearance. Cushion cuts are better for larger stones, and are available in both square and rectangles. Originating back to the 1700s, it was originally called the “mine cut” because of the square shape and rounded corners. It was named after the Brazilian diamond mines and was one of the more popular cuts until the late 19th century.